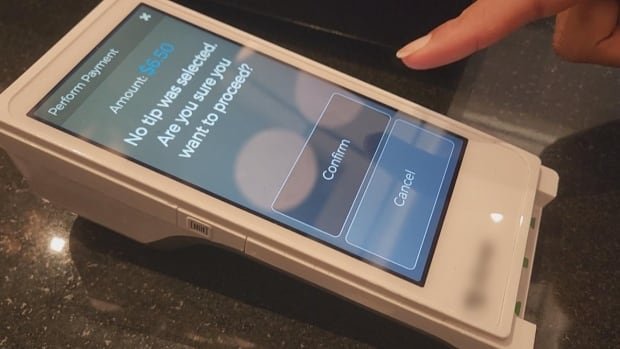

Be it buying a burger and fries or getting your car repaired, enter your credit or debit card into a machine and you might get a not-so-subtle nudge: how much would you like to tip?

But a hidden camera investigation involving 100 businesses by CBC’s Marketplace has exposed there’s no guarantee the tip you leave is going to the person it was intended for.

CBC journalists went undercover, posing as consumers, to businesses — including sit-down restaurants, fast food, retail, auto service centres and self-serve kiosks — counting up who’s asking for a tip, why, and where all that extra money is really going.

While it’s illegal for employers in some provinces to pocket tips, front-line employees say it’s still happening: the undercover team heard that complaint at six Ontario fast-food establishments, while research found that hundreds of employees have filed complaints of their tips being held back in Ontario and other provinces that have similar tip-protection legislation.

Marketplace is not naming the businesses it visited in an effort to not identify the workers who spoke to undercover journalists.

“Some of those places are actually breaking the [employment standards] law, but it’s easy to hide,” says Michael von Massow, a professor at the University of Guelph who studies the economy of food and tipping.

During the Marketplace spot check of 100 Ontario businesses, workers at six fast-food restaurants told undercover journalists they don’t keep their tips.

The complaints come as Canadians are leaving bigger tips than before.

Square, a technology and payment services company, says the average tip in Canada left on its platform jumped from 16 per cent in 2019 to 20 per cent in 2023.

Tip prompts appeared on payment terminals at 72 out of 100 places visited in the spot check, with suggested tip amounts ranging from five per cent up to 30 per cent. The machines also included options to leave a custom amount or no tip.

And the scope of where people feel pressure to tip is growing, too, says Marc Mentzer, a professor of human resources at University of Saskatchewan’s Edwards School of Business who has studied tipping.

“The phenomenon of tipping is spreading to transactions that would never have been considered … five years ago,” he said.

Who’s asking for tips and tipping on tax

Marketplace uncovered tip prompts at places you might not expect — or where it’s unclear what the tip is for, including an auto service centre, a wedding dress shop, a jewelry store, online merchants and self-serve kiosks.

Mentzer said it’s “utterly ridiculous” to tip for services like these, because they’re services that you wouldn’t expect to be asked for a gratuity or involve no human interaction.

“Where does this take us? Will we be expected to tip when buying groceries?”

In response to the findings that nearly two-thirds of retail, online and fast-food businesses visited prompted for a tip, the Retail Council of Canada said it “has not heard or seen any indication of wide-scale tip-prompting” among its 54,000 members. The association, which represents businesses including online merchants and quick-service restaurants, did not comment when asked about complaints from some front-line workers saying they do not keep their tips.

Marketplace also noted several payment terminals calculating the tip amount on the bill’s after-tax total — something Mentzer and von Massow say is common.

“I think most people have no idea that they’re tipping on the tax … it does add up and people don’t think about it,” von Massow said.

Quebec became the first of Canada’s provinces and territories to ban tip calculation on the total after tax, passing legislation in early November. It will come into effect in May, according to the province.

Inconsistent tip protection laws

Unlike the U.S., Canada has no federal tip protection laws, leaving it up to provincial jurisdiction.

In P.E.I., Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador and New Brunswick, employers can’t take a cut of tips workers earn.

In Ontario and B.C., employers are only entitled to a portion of tips if they directly help customers.

In the remaining provinces and territories, there are no tip-protection laws.

At the six fast-food restaurants where workers told Marketplace they don’t keep their tips, some appeared to not understand the rules around tipping, with one asking the journalist if they are indeed supposed to be getting them.

Two of those restaurants told CBC they’re investigating further as their employees should be getting the tips, two say their staff were misinformed. One of those restaurant owners admitted to using tips to pay for some business expenses but will no longer do so, since the regulations state this is not allowed. The remainder did not comment.

Ontario has received 796 claims this year from workers who say they aren’t getting their tips; of those, 96 resulted in violations. The Ministry of Labour wouldn’t confirm how many complaints were closed without violations.

The ministry said in a statement it has made enforcement stronger by introducing tougher penalties for employers who violate the Employment Standards Act.

Mentzer said it’s worth noting some employees don’t know their rights and may not realize they are owed tips.

He also said many may not speak up out of fear they’ll lose their job.

What’s behind the change in tipping culture?

Tipping culture, von Massow says, has morphed as more people started using credit and debit cards, allowing the machines to ask customers for tips.

That unsubtle coaxing puts more pressure on consumers to spare some cash, compared to just putting out a tip jar, he said.

And during the pandemic, people tipped higher amounts — largely to help businesses fighting for survival amid safety measures and restrictions.

“I think we expected when things got back to ‘normal’ that it would go down again,” von Massow said, adding that businesses noticed higher tip amounts and acted on them.

When Marketplace visited sit-down restaurants, most asked for a 15 or 18 per cent tip on the low end, with the highest being 20 or 22 per cent.

“Honestly, tipping culture has gotten outrageous,” one server said.

It’s the increased tip amounts that have prompted some businesses to start raising the tip options on machines, according to Restaurants Canada, the industry advocacy group representing more than 30,000 food-service businesses.

Marketplace set up a holiday store loaded with hidden cameras and buried mics to find out how much people are willing to tip for very little service.

At the same time, people can still choose what amount — if any — they tip, says Restaurants Canada, noting a tip should reflect the customer’s experience and the entire process should be transparent. It also condemns any employers who withhold tips from their staff. They also recommend their members provide a range of tipping options including “other amount”.

The organization adds a survey of 1,500 Canadians it conducted in June 2023 showed about one in five respondents aren’t tipping as much at sit-down restaurants to try and save money.

Mentzer and von Massow said another contributor to tipping culture has been how much servers get paid.

Some provinces used to have a lower minimum wage for tipped employees, like alcohol servers, under the assumption the tips would supplement their pay.

In Ontario, for example, tipped employees have been getting at least minimum wage since 2022.

Quebec is the only province that still has a lower minimum wage for workers who have the potential to earn tips.

Advocates call for tip-protection laws and higher wages

Sydnee Blum, executive director of the Halifax Workers’ Action Centre, says “tip theft” has been a growing concern in Nova Scotia.

She said the group surveyed workers last year and found 73 per cent of respondents said they or a co-worker have had their tips “stolen” before.

“It’s not just workers at fast-food industries, it’s not just workers at high-end restaurants … it really is widespread,” she said. “If we’re looking at the course of a year, sometimes it can be thousands of dollars.”

Blum supports having laws that make a tip part of a worker’s wages.

- Get the news you need without restrictions. Download our free CBC News App.

Carolyn Krahn, executive director of the Workers’ Resource Centre in Alberta, is calling for similar legislation in her province. She added “tip theft” is hitting some people harder than others.

“Newcomers to Canada are often more subject to this type of exploitation,” she said.

The ministries responsible for governing wages in Nova Scotia and Alberta both said tips aren’t considered wages and aren’t protected by legislation, but they’re keeping an eye on the situation.

Blum, Krahn and von Massow said paying workers a living wage would also help combat tipping culture.

A living wage is the hourly pay workers need to pay their bills and participate in their community, according to the Ontario Living Wage Network. The living wage varies by city.

Mentzer supports tip legislation in each province and territory but said he doesn’t think a living wage would improve tipping culture — especially given people are tipping higher amounts now despite a higher minimum wage.

Blum and von Massow say customers should ask workers where their tips go.

Mentzer says consumers have a choice and shouldn’t let tip prompts influence them.

“Customers collectively need to draw a line in the sand and say some transactions deserve tips and others do not.”