Rwandan health authorities will begin a vaccine study against the Marburg hemorrhagic fever as the East African country tries to stop the spread of an outbreak that has killed 12 people.

Rwanda, which received 700 doses of a vaccine under trial from the U.S.-based Sabin Vaccine Institute, will offer it to health workers and emergency responders as well as individuals who have been in contact with confirmed cases. There is no authorized vaccine or treatment for Marburg.

The Rwandan government said Monday there were 56 confirmed cases, with 36 of them in isolation.

Marburg has a fatality rate as high as 88 per cent.

Marburg symptoms include high fever, severe headaches and malaise within seven days of infection and later severe nausea, vomiting and diarrhea.

It is transmitted to humans by fruit bats and then spreads through contact with the bodily fluids of those infected.

Neighbouring Uganda has suffered several outbreaks in the past.

Rwanda is starting a Marburg vaccine trial on health workers as the country fights an outbreak of the Ebola-like virus that has a fatality rate as high as 88 per cent.

Rwandan Health Minister Sabin Nsanzimana said the vaccinations started on Sunday.

“We believe that with vaccines, we have a powerful tool to stop the spread of this virus,” Nsanzimana said at a news conference in the capital, Kigali, on Sunday.

Previous outbreaks controlled without vaccine

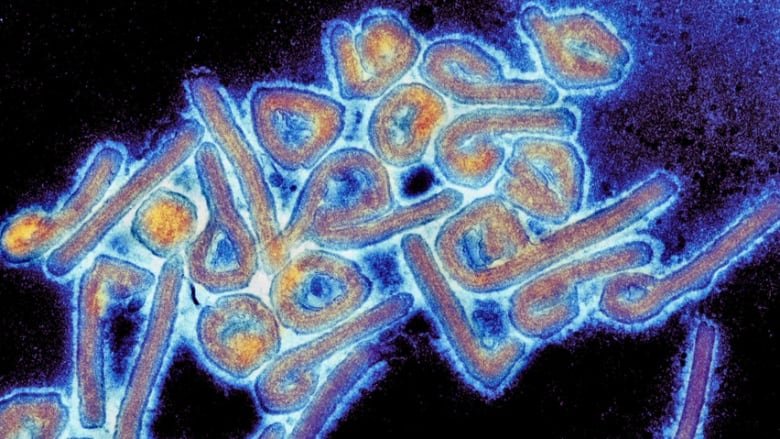

Dr. Isaac Bogoch, an infectious diseases specialist at Toronto General Hospital, said Marburg is closely related to Ebola.

Rwanda has enacted very strict infection prevention and control measures to significantly reduce the risk of transmission, Bogoch said, and is informing people throughout the country on what signs and symptoms to watch for and when to seek care.

Last week, Dr. Mike Ryan, executive director of health emergencies for the World Health Organization, told journalists Marburg exploits situations where there are failures in infection prevention control, including at sophisticated hospitals, on top of community transmission.

Standard public health tools like contact tracing and early detection and care have stopped transmission and saved lives during previous Marburg outbreaks. The experimental vaccine is an additional tool, Ryan said.

“As as terrible as these outbreaks are and as devastating as this infection is, it still is an opportunity to do good for this world by determining if these products actually work,” Bogoch said of the trials into Sabin Institute’s experimental vaccine as well as two potential therapeutics.

Marburg outbreaks and individual cases have in the past been recorded in Tanzania, Equatorial Guinea, Angola, Congo, Kenya, South Africa, Uganda and Ghana, according to WHO.

The virus was first identified in 1967 after it caused simultaneous outbreaks of disease in laboratories in Marburg, Germany and Belgrade, Serbia. Seven people died after being exposed to the virus while conducting research on monkeys.